The Structure of a Photograph

The structure of a photograph is founded on light. It starts out with seeing that light and then building up from there. Seeing the light however, is where most of the real work behind a photograph takes place. Some say seeing photographically is inherent and can’t be taught. I am not of that bent. I think anyone can be taught how to make great photographs. There are a number of skills that are required to make great photographs and all of those skill can be acquired.

Photography is writing with light and so it should go without saying that a photograph will convey something to the viewer. What a photograph conveys will depend on the intent of the photographer. No matter what the photographer wants to say, and whether the photographer knows it or not, every photograph is made from both a top-down and a bottom-up process.

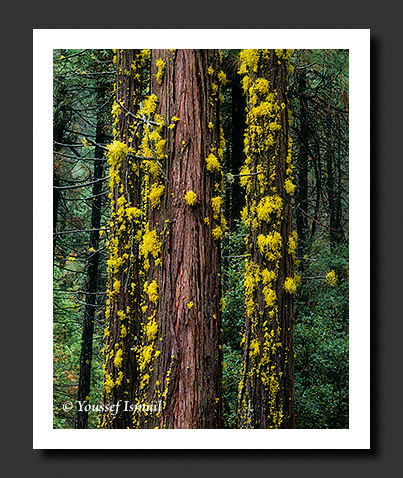

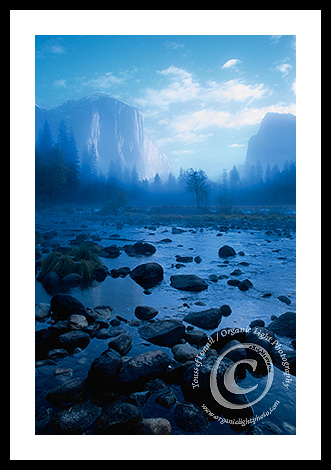

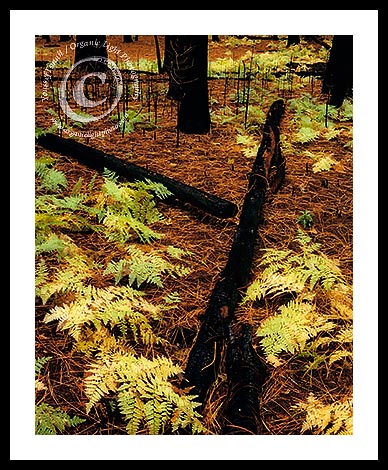

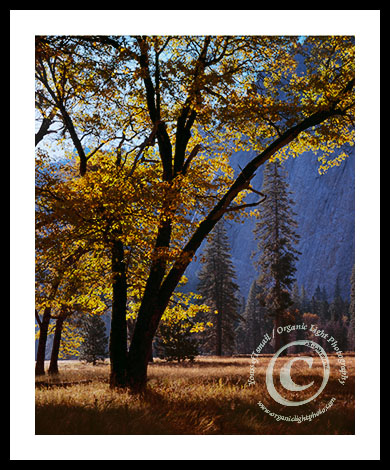

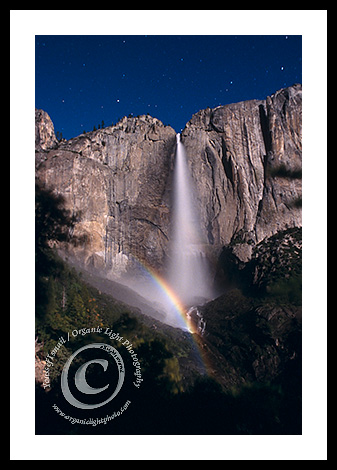

Whether the photographer is conscience of the top-down process or not, it all begins with seeing light. Something will catch the eye or interest of the photographer and causes the process to begin. Is the light warm or cool, is it harsh or soft, is it diffuse or directional? What elements are illuminated by that light; lines, shapes, colors, textures? Spatial relationships begin to form between the graphic elements and the geometry of the image starts to take shape. At this point the photographer might consciously or unconsciously start to look at the scene from the aspect of isolation. How can what is seen be isolated from its surroundings or on the converse how can it be incorporated into its environment. This will prompt the photographer to start on a more technical path of choosing a lens to either limit the angle of view or expand it. Not only will the lens choice determine the angle of view but it will also dictate the perspective taken, that is where will the photographer stand to make the photograph.

Once the lens and perspective are chosen, the next decision, although technical in nature, has artistic consequences and this is the selection of the lens’s aperture. The technicalities of photography now start to emerge and lacking the technical knowledge will usually be the reason a photograph fails to convey the photographer’s intent. For now the photographer has reached the bottom of the top-down process.

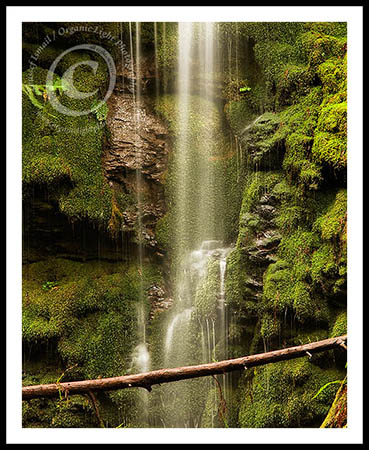

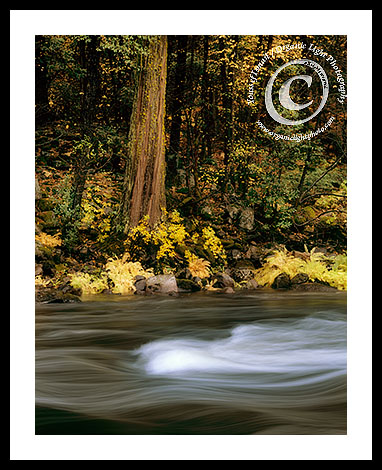

Tailbone Falls - Early Winter run

Upon choosing a lens it must be focused and its aperture set to a given size. It is at this point that the photographer begins the bottom-up portion of the photography process. The bottom-up process is one of technical skill in working with the light itself – from determining how much light is available to how much to let into the camera and for how long. And unfortunately it is at this very point that most photographers start the image making process and also where confusion and failure start. It all begins with choosing the aperture, then based on the light available, the shutter speed is determined and coupled with the sensitivity of the capture medium, forms what is called an exposure.

The aperture of a lens is that physical parameter that will ultimately determine how much light will get into the camera to make the photograph a reality. A large aperture will let in more light than a smaller one. While a smaller aperture will, for that given lens, increase the depth of field and a large aperture will limit the depth of field. This property of optics, depth of field, is the perception of how many elements in the scene will appear to be in focus. As technically only one distance from the camera will actually be in focus – the distance focused to on the lens, all other distances closer to and further from the camera will not truly be in focus. The size of the aperture will either enhance the perception of focus or reduce it.

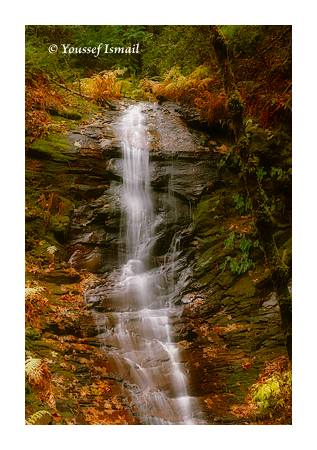

The shutter speeds determines how long light will be let into the camera to expose the light sensitive medium. The shutter too has both technical and artistic consequences. Where the aperture was concerned with the perception of focus, the shutter deals with the perception of time. Time is an interval over which some action takes place. The shutter speed chosen will either elaborate time by showing action occurring through the perception of motion-blur or remove time from a scene by freezing objects in the frame. With a fast shutter, in other words allowing light to enter into the camera for a very short amount of time, motion can be stopped and time frozen in that instant. Conversely, with a slow shutter, one in which the lens is open for a very long time, any motion occurring in front of the camera will be captured as such and give the perception of action occurring.

So as the technical settings are set, the photographer still needs to be thinking about what he or she wants to convey in the photograph and how. In addition to that, determining the right amount of light to let into the camera is of probably the most important step in the bottom-up process. Determining this amount of light is what most call exposure.

Unfortunately it is the failings of understanding the basics of exposure, the very foundation of capturing the very light that caught the photographer’s fancy in the first place, that renders a photo unsuccessful. It is here that the foundation of any photograph is formed. By observing the light, measuring its intensity with a light meter and setting the tonality of the subject being photographed to a tone that comes as close to how the photographer’ eye sees it, the photographer can start building up the photograph so that it can convey his or her intent. Once the tonality of the subject is assessed and set on a tonal scale where the ends of the scale are pure black and pure white now allows the selection of the aperture and shutter speed such that the tonality of the subject is rendered as seen in the resulting photo. With the first photograph formed, the photographer can asses if it resulted in conveying what was originally ‘seen’, and if not variations in either the technical or creative elements will be made until the image is deemed successful.

The entire process could take moments, hours, days, months or even years to make one successful photograph of any given subject. Learning the photographic process is a long term endeavor. Learning how to make good technical photographs takes a person on a journey through the bottom-up process of understanding light as a physical quantity, learning how to measure it and control how much gets into the camera and how it will look in the final photo. Learning how to convey what is seen, or even more difficult, learning how to see in the first place requires a person to be immersed in the light and look at it over and over and cognitively observe how it effects mood, emotion and state of mind.

It is a step by step process that can provide a lifetime of learning and enjoyment. Taking it stepwise in concise classes or in an intensive immersion in the whole process with an instructor devoted to communicating with light is right way to proceed. Organic Light Photography offers many such classes and workshops. In addition if none of these offerings suit you, contacting us about what you want we can tailor instruction to your needs and if not we can recommend other fine instructors that can help you. It all starts with you.